Nordic Film Days, Lübeck, Germany, October 2022

By Paul Caspers

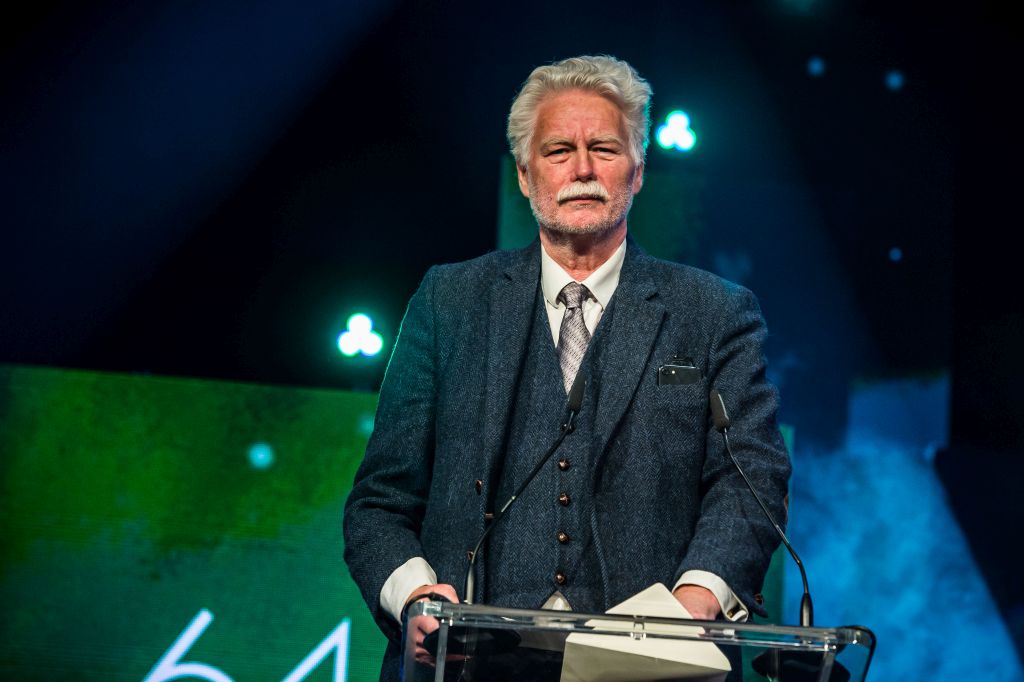

Iceland’s greatest director came to the Lübeck, Germany’s annual Nordic Film Days, the world’s premier event for Scandinavian cinema, to accept an honorary award, and to present five of his feature films. Friðrik Þór Friðriksson is a veteran of the festival: some of his very first work was screened there, and he’s been a regular visitor and a recipient of several prizes in the four decades since.

Mild panic set in when he didn’t show up for a Q&A after a screening and the subsequent interview appointment, but a new date was arranged and the director sat down for a short, amiable conversation. Though fluent enough in English, he preferred to speak Icelandic, so the quotes in the following are my own translations.

He says the audience response to his films now is exactly the same as it has been over the past decades. But what about the man himself? Friðrik’s belated debut feature was White Whales, released in 1987 after a string of highly unique short films made since 1980. (It wasn’t part of the small retrospective, although it did win the audience award at the Film Days.) Its doom-laden tale of two despondent whale hunters ends in hyperbolically violent death, and compared to the mildness of his last feature 2010’s Mamma Gógó, it seems like an angry, deliberately provocative film. But the producer-director says he was much the same man as he is now, and reminds me it’s based on actual events. In the opening credits, his own name appears below that of the novelist Einar Kárason, who co-write several of Friðrik’s other films, and he tells me he’d given a ‘skeleton’ version of the story to the author, who expanded the material. “Each film needs its own approach. Falcons [2002], which I also did with Kárason, was the same: the structure was in place and he fleshed the whole thing out.”

Of course, almost all of the other features are co-written by the other novelist, Einar Már Guðmundsson. I wondered if his collaboration with the two men is very different. “Very much so. With Einar Kárason, I meet up with him, usually in the countryside, and then he goes to work with what we’ve discussed. When I collaborate with Einar Már Guðmundsson, we’re together all the time. But the films I’ve done with him are quite different. Angels Of the Universe [2000] is based on his novel. We’ve been friends since we were 8 or 9 years old, and I knew his brother, the subject of the book—I went to his home, I knew his whole family. With Children Of Nature [1991], I’d applied again and again for funding from the Icelandic Film Fund with a script that was too short, only about 45 pages. So Einar, who was a professional writer, jumped in and helped out to flesh out the story. It was the same with Movie Days, which was built on my own memories. The basic structure was created by the cinematographer Ari Kristinsson and me.”

The idea for his most recent feature Mamma Gógó (2010), which toys with memories of his own career as well as memories of his mother, came to him during a visit to a stonemason who made gravestones. “My mother was always forgetting her keys and thought my brother was stealing them from her. It was the first clue that she was suffering from Alzheimer’s.” Mostly, though, he made the film to focus attention on the issue of dementia. “I figured society wasn’t aware of Alzheimer’s, just as it wasn’t aware of schizophrenia when I made Angels Of the Universe. Alzheimer’s is very common—so many people have it. But they were just put away, just like those who suffered from schizophrenia. Patients were just drugged and locked away. I’d just made a documentary about autism [2009’s The Sunshine Boy], and the exact same thing was happening to people who suffered from that: they were locked up. So I was concerned with making films about the brain, which we know so little about. We know more about the moon than about the human brain.”

Friðrik hasn’t made a feature since 2010—although he adapted a crime novel for television and made a documentary about the Icelandic painter Georg Guðni—and with its retrospective qualities, Mamma Gógó could seem like a fitting end to a distinguished career. But it won’t be: Friðrik is busy as ever getting films off the ground. “I always have about five scripts on hand. And then there are several authors I’d like to adapt. I had a film in mind based on a book by the poet Stephan G. Stephansson. But after a while you realize the films would be so expensive that they might never get made. I have to work with scripts for cheaper films, and that’s what I’m doing. I’m going to work with a script by the novelist Gerðir Eliasson and make an affordable film. And I’m trying to make a film with Einar Kárason, based on his novel The Promised Land.”

“I also started producing again. I produced a film based on the novelist Guðbergur Bergsson, directed by Ari Alexander Magnússon [Loss], who I made a couple of documentaries with. It’s shot and edited; it just needs to be soundtracked. It should be out in a few months.”

It’s well known that Friðrik has long had ambitions to direct a Viking film, even predating his earliest shorts—but money is still an object. “I wrote scripts for Viking films, but they were too expensive to make. I still have them! It’s good stuff. I received funding from Iceland, but the money from abroad is lacking. I would still like to do it. I’ve always had this idea that the Icelandic Sagas inspired westerns and film noir. Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett read Egil’s Saga when they were writing. It’s been proved that they read it when they were writing their books in the Santa Monica Library. And John Ford was very fond of the Icelandic sagas, as was his editor Robert Paris. And of course Kurosawa was fond of Ford, and Sergio Leone was fond of Kurosawa…”

Other Icelanders have attempted to make Icelandic ‘Viking films’, most notably Hrafn Gunnlaugsson. “I worked with him on an original outline for When the Raven Flies (1984). But you have to come up with something original, like Leone did with Morricone’s music. Hrafn didn’t come up with anything original in the film. I guess he didn’t understand what I wanted. And it’s basically a Swedish film. It looked like he made sacrifices to the Swedes.” Likewise, Friðrik points out that the two much younger Icelandic writer-directors also present in Lübeck, Guðmundur Arnar Guðmundsson and Hlynur Pálmason, went to film school in, and are financially supported by, Denmark. He has nothing but praise for their work, though, and is anyway pleased with the remarkable success that Icelandic cinema has had in the past few years. “Icelandic filmmaking has improved a lot. I’m very satisfied with the great majority of it today. Especially the women. When I was teaching at the Icelandic Film Academy in the past four years, there were many excellent women, with a strong poetic sensibility.”

///

Link: Nordic Film Days